About Javier Arrés

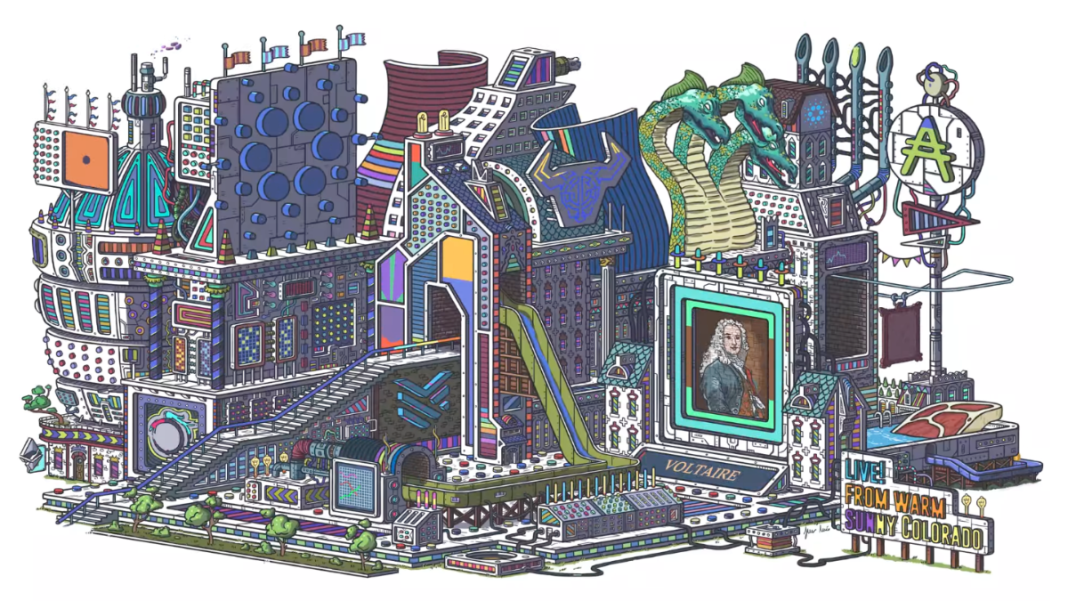

Javier Arrés is celebrated for his “Visual Toys,” intricate illustrations of fantastical cities and complex machinery that invite viewers to explore their imaginations. Merging his Andalucían heritage with modern digital techniques, his style—termed “pop baroque”—reinvents traditional aesthetics for the digital age.

In this interview, Arrés dives into his latest sculpture series, the MECH Army and the thought process behind its creation. He describes the series as a blend of historical influences and futuristic design, expanding his signature style, portraying mechs not just as machines but as cultural icons, imbued with the narratives and aesthetics of a world that merges the ancient with the futuristic.

Brady Walker: Welcome back to the Makers Place interview series. Today, we have with us Spanish artist Javier Arres. Javier, could you give us a little elevator pitch about yourself as an artist?

Javier Arrés: Happy to be here. I began my artist career very early, starting with painting at 11 years old. I’ve always been interested in art and creativity. I worked as a professional illustrator and graphic designer for many years, collaborating with two important agencies. I’ve done work for the New York Times, Corriere della Sera, and other notable clients. Alongside, I was developing my own style and vision as an artist.

There was a time when I was unemployed for a few months between jobs, and I decided to paint something huge on ink paper. I’ve always worked both digitally and traditionally. That work won me a prize in the ink paper category and marked a significant point in my career. I also had the honor of being the first international artist invited to the first GIF festival in Asia.

Later, I received an email from MakersPlace in 2018 about NFTs, which significantly changed my career trajectory. Since then, I’ve created several digital works and launched successful collections with MakersPlace. Today, we’re discussing my latest, the MECH Army collection, which combines 3D printing and digital art in what I call a ‘phygital’ collection.

BW: Your work is incredibly intricate. I especially think of your pencil and ink works on Makers Place. It’s like compressing an entire comic book or graphic novel into a single page. Your pencil style particularly reminds me of R. Crumb. It’s an easy comparison to make. Do you have a lot of comic book influences?

JA: Yeah, not too much, to be honest. I think it’s more influenced by movies and video games, but comics as well. I’m from a small city on the southern coast of Spain. Born in ’82, I grew up in the ’90s. It wasn’t easy to find many comics there. In the US, you might find a comic shop everywhere, but it was different in my city. However, I remember some comic fairs, small ones like book fairs with comic stands.

So, while I have some comic influences, my bigger inspirations are from TV, movies, or video games. For instance, Back to the Future — I must have watched it a hundred times. American movies have greatly influenced my style, along with a few underground Spanish ones. Movies are really significant in shaping my style and life.

My art is a mix of many things. I don’t discount anything. For example, you can see my interest in architecture in my work. I’m originally from near Granada, and now I live there. It’s one of the most beautiful cities in the world for architecture. So, I’m surrounded by it and inspired by architecture, movies, and video games, mixing everything into my work.

BW: Tell me about the MECH Army. Why did you create this series?

JA: The MECH Army is a huge collection because I always wanted to do something like that. This pieces are both digital and physical, which is a challenge, especially painting by hand. Painting by hand is difficult because you have to consider the physical aspects when designing digitally.

For instance, this piece has many parts, like the arms and legs, that need to be assembled. I talked with the print shop, and they were hesitant because it’s complicated and fragile. It’s important to understand that not all 3D printed sculptures are simple; many are basic, but this one is complex. It requires multiple paint layers to achieve the right color, which is not easy.

The MECHs reflect my vision of mechanical characters, influenced by my childhood in the ’90s and my fascination with robotics and mechatronics. I’m thrilled to have had the chance to create this collection.

The MECH Army isn’t just about toys; it’s about creating a narrative within my series of futuristic cities. I give my cities a culture and a history, making these MECHs like artifacts from the past for the inhabitants of my series. They might seem like pop culture to us, but to the people in my series, they’re historical, almost prehistoric figures. This collection is about integrating these elements into the deep cultural and historical narrative of my imaginary cities.

Imagine visiting a museum where one of these MECHs is displayed. It’s an ancient, iconic figure from that culture. This opens up the imagination: how was the past of this society? What kind of gods or heroes did they have? These MECHs are like gods or heroes from their past. They’re not just tools of war but are significant cultural icons, remnants of the past now shown today.

BW: I often find myself wondering what society would look like if Greek culture had outlasted Christianity, considering Christianity as just old mythology, and Greek mythology was still prevalent. What are your thoughts on that?

JA: Mythology is exactly the word I was looking for. For example, one of the artworks features a print of a city, a massive city with MECHs integrated into its structure, much like sculptures in ancient cities. It’s reminiscent of how the Greeks and Romans incorporated sculptures into their architecture. This artwork represents something ancient and important, more significant than just the present. I don’t have the finished print to show right now, but I can show a work-in-progress photo if you’d like to see it.

BW: Could you share your screen? There’s the…

JA: I’ll open Photoshop. With the print, we can understand better. It’s like you say, a kind of mythology. And, for example, in the Renaissance, Michelangelo created amazing sculptures that nobody can make today.

BW: It’s funny, I’m currently learning about opera and how during the Renaissance in Italy, everyone became obsessed with ancient Greek culture. Italian composers were puzzled by how music profoundly affected people in Greek culture and wondered how they could replicate that. This led them to essentially reverse-engineer what the Greeks might have done, and from there, they created opera.

JA: Yes, it’s an example of that, but I think it’s more romantic and soulful. Here, you can see the illustration; it’s huge. Discussing the MECHs, they are like sculptures from the past, akin to gods. You put it perfectly. Look here—this is the foot, and you can see it resembles a part of a park.

BW: This piece is huge and insane.

JA: It is a massive work. It’s like a park and has a mythological feel. It’s not finished yet; this is a work in progress. This is the Super General, and this is a city, and maybe they are gods. I never claim the absolute truth; I say maybe because for me, it’s crucial to leave space for people to imagine. That has always been important to me. It’s like a kind of mythology.

BW: Do all these visual toy cities have names, or are they all part of one giant city?

JA: That’s a good point. You can never see the end of the city; there may be neighborhoods or parts with names, for example, Capital City. But I avoid giving them specific names like Philadelphia because I believe that too much detail can limit the imagination. I prefer to leave it up to the viewer to decide if it’s a neighborhood or a city. My approach is to frame the artwork in such a way that it stimulates the imagination—whether it looks like a neighborhood or a downtown area, the actual scale of the city remains ambiguous.

BW: What’s the process of creating something so enormous and detailed?

JA: The first step is the concept, making sure everything is balanced. Once I have the concept, the work begins, not focusing too much on detail at first. I allow myself a lot of freedom in the design process, making sure the placement of elements like mechs and buildings is balanced. The most important thing for me is this balance; I visualize the city, adding elements like buildings and windows step by step. It’s not stressful for me; I enjoy it a lot. It’s about gradually adding to the city, balancing the main features and the details, maintaining harmony throughout the artwork.

BW: Does the MECH army have any personal meaning for you?

JA: Yes, I am passionate about MECHs and collectible figures, which are always thrilling to create. They’re a significant part of my personality and my work. Holding one makes me very happy; it feels like a part of myself. Just like designers see chairs as a challenge, with endless possibilities to create different designs, I see MECHs the same way. I could design thousands of them, each one showcasing creativity and passion for technology. They are a powerful way to express creativity, and I feel very comfortable and fulfilled working with them.

BW: What feeling or experience do you hope to create with your visual toys? What do you want people to take away from them?

JA: The experience is magical and imaginative, like having a piece of a fantastical digital civilization. Each MECH or figure can be seen as an ancient, unseen icon, representing something magical and significant. Although they are digital creations, they also exist tangibly in prints and sculptures, bridging the gap between digital and physical worlds. My hope is that people see these figures as historical artifacts of a digital culture, offering them a glimpse into a richly imagined world.

BW: What’s the most accurate thing that someone has said about your work?

JA: I read it described as ‘pop baroque,’ which I think is quite accurate. This description is significant to me because I was born not far from where Picasso was born, in Andalucía, a land for artists. My art involves complex structures, but if you look closely at the details influenced by the beautiful architecture of Granada, you can see elements of baroque style amidst the chaos. So, ‘pop baroque’ really encapsulates what I do.

BW: Do you have any rituals?

JA: I don’t have many rituals. I tend to work at night, although not exclusively. I’m a hard worker but sometimes I feel lazy, maybe smoking on the balcony. I drink a lot of tea to stay focused, as I work in a professional, structured manner, much like I did in graphic design. I often work with something in the background; I like having an iPad nearby to play movies that I’ve seen many times. It’s not really about watching the movie, but more about listening while I work, which helps me stay in a good mood and be productive.

BW: Do you have any idols or influences that might surprise your fans?

JA: Oh yes, it might surprise people to know I’m a big fan of football. Some might think that football doesn’t fit with elevated cultural discussions, but I really enjoy sports. If you want to grab beers and chat, talking about football is the best way to connect with me.

Artistically, I admire Goya — though his style is quite different from mine. I’m also a big fan of Federico Fellini and classic films, the very old ones, but those with timeless narratives. I don’t like superhero movies much; I agree with Scorsese’s view on Marvel movies being more like roller coasters than true films.

In my future work, you might see influences from darker themes. I’m interested in gory details and the psychological aspects of serial killers, which I know a lot about. This might come off a bit strange when chatting casually because it’s a rather intense interest, especially concerning American serial killers, which are well-documented in films, unlike Spain’s true crime stories, which have a different tone. So, this aspect of my interests might be surprising to some.

BW: What role does chance play in your work?

JA: There is definitely some serendipity involved. I consider myself quite lucky, especially in how my career has unfolded. For instance, I was working on visual toys and digital art for about six or seven years before the NFT market emerged. I developed my unique style well before there was a real possibility to sell digital artwork. I remember telling my wife years ago that if I ever made money from my art, it would be amazing because I was doing something new that I hadn’t seen anywhere else.

Another example of serendipity was when I created a large ink on paper piece while unemployed. Around that time, I received an email about a London exhibition I could participate in, but I had sent the invitation to my future self two years earlier, not knowing I would’ve had the time to make a big piece. Ironically, when I needed it most, the email arrived and I ended up winning the contest and selling that artwork for a good amount, which significantly changed my life.

Additionally, I once won a worldwide contest with a visual toy, earning 4000 euros. The prize money arrived three months later, exactly when the studio I was working for started to fail in paying its artists. This money allowed me to survive for three months while I looked for a new job. It was incredibly fortunate timing and felt almost like destiny.

For updates on all of our upcoming editorial features and artist interviews, subscribe to our newsletter below.