“I always try to learn something new with each piece. If I don’t learn something, the work isn’t that good.”

— Quantum Communications

About Quantum Communications

In this interview, Quantum Communications, known in the graffiti world as waxhead, discusses his artistic evolution from street art to digital creation during the COVID-19 lockdown. Using Blender and the MidJourney beta, he created a space for himself with digital art to explore new styles and emotional vectors. His unique approach incorporates a grainy, VHS-like texture, giving his work a touch of nostalgia and realism.

Quantum’s digital pieces explore the concept of liminal spaces—transitional areas that evoke intrigue and unease. These themes resonate throughout his work, combining elements of reality and surrealism to challenge viewers to reconsider the spaces they inhabit. His use of liminal horror aesthetics invites a deeper engagement with the eerie and the overlooked in both digital and physical landscapes.

Brady Walker: Tell me a little bit about your background in the arts.

Quantum Communications: I started predominantly as a graffiti and street artist. During COVID, I got my first PC and began messing around in Blender, doing a lot of 3D scanning, and got into the MidJourney beta. I started experimenting with these tools, maintaining the playful character and cartoon style that I had been working with, which was heavily influenced by graffiti.

Spending more time online, I came across a lot of liminal horror and dream core aesthetic art, which really attracted me. So, I decided to use Blender primarily as a learning tool at first. I thought, “I could create these spaces in 3D and learn about lighting, composition, and Blender usage.” This eventually transformed into me creating different stories and finding my own aesthetic within the broader range of liminal space artwork.

BW: Yeah, I was going to ask about Blender because a lot of the stuff I’ve seen goes for a glossy feel, which makes it feel 3D. Your work, however, has this graininess like an old VHS tape.

QC: Yes, that grainy aesthetic, it’s almost easier for me to fake a sense of realism with it. The graininess lets the brain sort of fill in the missing pixels and achieve a more realistic feel. I add the grain, VHS effects, and play around with the lighting and effects post in After Effects.

BW: Yeah, definitely liminal. Can you define liminal space as you use it in your work?

QC: A liminal space is a transitional space, essentially void of living beings. Sometimes I include living organisms, like plants or plant-like creatures, but it’s more about being a space between spaces, or a place between times. For example, we have our life at the office or during our commute; these are transitional spaces. They serve a purpose but aren’t meant to be lived in completely. They are intriguing places to explore. I do a lot of urban exploring, especially with graffiti, so these spaces are areas you can traverse and experience but not inhabit permanently.

In my series of artworks, these are places you visit but wouldn’t live in. Take, for example, a completely unpopulated eerie subway station where trains move but there are no people—it’s very creepy.

It’s like the movie 28 Days Later. I love the opening scene because you see London completely empty, devoid of everyone. That eerie, creepy vibe of liminal horror and strange spaces really attracts me. My interest in this definitely spiked during COVID due to our isolation. It’s also a departure from the happy, colorful, cartoony artwork I used to create for a long time. It’s refreshing to express my emotions through a different voice that perhaps wasn’t possible with my earlier body of work.

BW: I’m curious about the liminal spaces and liminal horror. This is a new genre to me. Can you tell me some of the artists and sources of inspiration in this genre?

QC: I’ve been greatly inspired by artists like Kane Pixels. He’s actually making a film with A24 about “The Backrooms,” an internet series that became quite popular. It’s about a place where you fall between reality into these plain rooms, all created in Blender. There’s a horror aesthetic, with monsters chasing someone through these spaces. Kane’s videos are beautifully woven with a narrative throughout the series, so he’s a major inspiration.

Another influencer is an Argentinian artist known as Everlasting Building, who was releasing work on Tezos a lot in 2021. This was before I started creating many liminal spaces, but he was a big inspiration and a good friend. Films like The Blair Witch Project, Gozu (a Japanese Yakuza horror movie), and Beyond the Black Rainbow are probably my biggest inspirations for liminal spaces in film. I travel a lot and go to many airports; the architecture and spaces there also provide significant inspiration.

BW: What are your ambitions combining Blender, video, and AI in your artistic practice?

QC: I’ve been experimenting with AI since the MidJourney beta, and I realized that I could input video or frames from my Blender pieces into DeForum. This exploration with Stable Diffusion interpreting my images has yielded some really amazing results, almost like everything is flowing together. It’s hard to explain, but there’s this sense of exploring a de-realized space within these liminal spaces. It’s really cool.

On my daily.xyz page, the first series I did involved a lot of this. There are a few other videos where it was like navigating between the latent spaces and real life—or rather, Blender-rendered life. I’m treating them almost like Schrödinger’s cat experiments, seeing what emerges between the prompt and what I’ve created, how the original image can transform yet remain fundamentally the same.

I’d love to see something like A Scanner Darkly, where they rotoscoped over all the footage with the suits that are constantly changing faces, capturing this uncertainty of identity. It ties into the quantum concept—everything is just particles that are loosely connected. In this latent space, I can almost create that vast, ambiguous space within the pseudo-Schrödinger’s cat experiment of AI.

BW: The Quantum Institute feels like there’s a bigger story to tell there. Is this something you’re planning to elaborate on? Are there bigger scenes to look forward to?

QC: I think it would be really nice to do more narrative-driven artwork. It’s definitely something I’d like to approach more in the future. I wouldn’t consider myself the best storyteller; sometimes I think of storytelling as a game of broken telephone. Often, I’ll start something but might not always finish it, trying to connect it to other pieces in the series. Having a theme like an evil corporate workspace has been something I’ve dabbled with throughout my pieces.

I’d like to maybe develop a more cohesive narrative in the future, perhaps with The Quantum Institute. That series was specifically about a collection of different cults and short descriptions of them. There’s The Fellowship, a play on all our weird AI guys doing fun stuff, and The Herbalists—here in Canada, everybody’s smoking weed all the time. I’m fascinated by cults and the different systems people embed themselves in, whether corporate systems or more hippie-oriented stuff.

BW: Yeah, they’re both interesting systems of control, and similar in a way. I see the dystopian potential in your genetically engineered protein animals, which seems potentially more interesting than the Quantum Institute, as it’s unique to you. Can you tell me about that piece, where it came from?

QC: Oh, yes, that idea is like the Soylent Green of our age. It originated from envisioning a corporate or pharmacological corporation that dominates everything, thinking about what we’ll need in the future. Like in the new Blade Runner, there’s a scene at the beginning where they’re eating worms from a worm farm because that’s all that’s left. The protein animals could definitely be possible in the future with the right genetic manipulation. We’re already seeing lab-grown meat.

Inspirations for that came from various movies and lab-grown meat. My ex is a vegetarian, so we ate a lot of fake meat, and I was poking fun at that. Also, I used to go on long drives to visit my grandparents in the countryside, imagining large creatures walking through the landscape as I stared out the car window. Those drives influenced how I envisioned these creatures moving through suburbs or farmland, reminiscent of those trips up north to my grandparents.

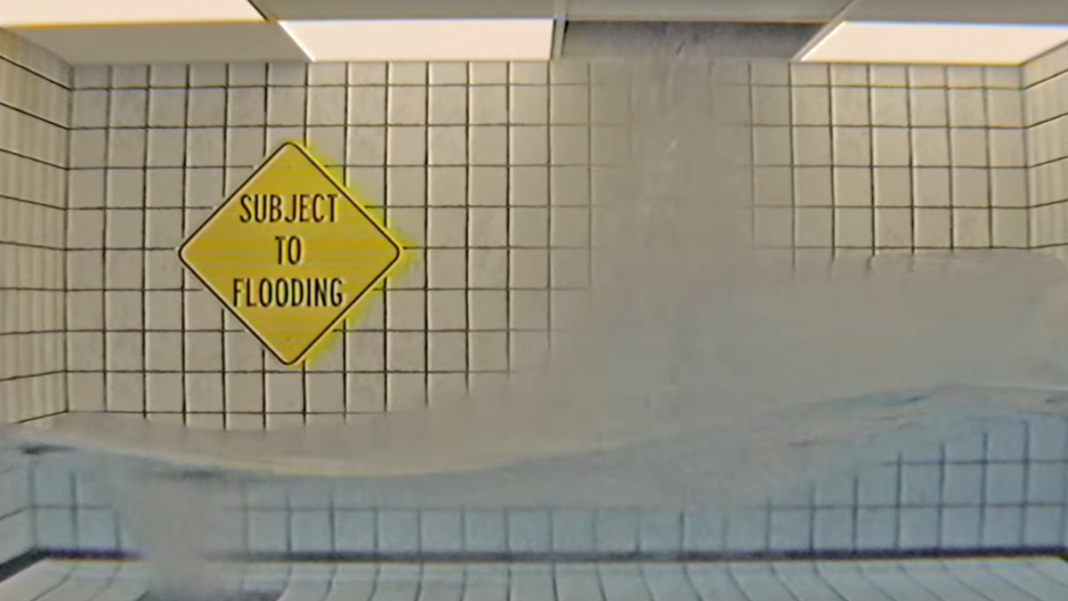

BW: Subject to Flooding is perhaps my favorite piece of yours because it’s just so hilarious. It has this deadpan humor. Why would this space flood? Why does it exist? Who would enter a space that is subject to flooding? It’s a quick setup followed by a really long punchline, just watching the water flow. I laughed out loud when I first saw it. Can you tell me about that piece in particular?

QC: That’s definitely a really fun piece. I love how it takes on almost a joke without having to explicitly say anything. You just see the small sign and a warning sign. I sometimes think that all these spaces, all these rooms, all these artworks I’m showing are connected. They might be part of one corporation or a group of corporations performing different tests—no one knows what those tests might be for.

Why is the room flooding? Maybe it’s an exhaust for some other room or project. But the simplicity of it is fun. I was playing with the water physics; I got a really good handle on water physics and was experimenting with that. I always try to learn something new with each piece. If I don’t learn something, the work isn’t that good. So, I wanted to play with water physics.

I see myself in the artwork almost as a scientist or one of the employees, and I talk to people on Twitter like that, saying, “Thank you, loyal Quantum Communication employees.” It’s like we’re all employees working in this corporation, building this narrative I’m loosely trying to create. That’s how it fits in with the rest of the work.

BW: The other piece reminds me of Got Milk?, which also features flooding, and Home. Can you tell me a bit about the genesis of those pieces?

QC: Those pieces are all within what I call ‘the room,’ similar to jjjjohn’s windows. They were inspired by his work and are set in a controlled environment. I work within that cube space, angling the camera to make it my experimentation space. Actually, when I start up Blender, that’s the scene I begin with: The Cube. I start with a cube and then either expand to a larger room or stick with that one space for experimentation. I maintain the old office classic lighting because I love how the light bounces off things, using it as my base for whatever I’m creating.

Home and Got Milk? were about playing with that space. Home, specifically, is very isolating and controlling—it locks you in with its walls. I find that powerful. It reflects how we’re all somewhat locked in our spaces in life. It’s difficult to escape the box we put ourselves in, whether that’s good or bad. Some people might be happy in their box, while others might not.

BW: Yeah, it’s definitely claustrophobic. Then you have this other series on MakersPlace like dark mahogany rooms that includes Towers and Classical Pepe. It makes me think that, if the other pieces are in this dystopian corporate office, this is like the boss’s house, where you’re invited to drink blood or something. Can you tell me about these pieces? Were you exploring the lowest lighting you could find?

QC: To the point where I can’t even see anything. Some people were upset when I released those, wondering, “What the fuck is this?” But I really love them. I tried to recreate classical paintings using AI. As an art lover, I’ve always been floored by visiting grand museums like the Louvre and seeing the masterworks. I imagined a place where people had stolen some of these artworks and placed them in dark rooms for the most opulent of bosses to go down, light their cigar, and stare at the painting for hours while plotting. This series was planned around that feeling. I wanted to create big, grand artworks and see how it felt being in that kind of space.

BW: What is the role of titles in your work?

QC: I think usually the role of titles is to convey a message, though I wish I didn’t have to include a title most of the time. I prefer the work to speak for itself. But a title gives a loose direction to the viewer, maybe ties it in somehow. Sometimes I like to write a small blurb or a story in the description instead. I would prefer our work without a title, but I usually pick something that can convey more of a story, which is even more powerful than a title itself.

BW: Whom are you working with or thinking with lately?

QC: Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot with my buddy Strano. He’s doing some beautiful, architectural brutalist artworks and he’s always a good person to chat with. I’m also typing with my friend Noper often; he’s doing some beautiful AI liminal works.

BW: What is your great unrealized project?

QC: My great unrealized project involves needing to level up some of my skills first. I want to blend AI more into my artwork in ways that complement each other better. I have a lot of ideas for new artworks, but I need to enhance my skills to realize them.

BW: So what exactly is that unrealized project?

QC: Oh, sorry. It involves a lot of plants, rooms, and steam—steam room plants, that’s all I can say for now. I want more movement and rigging within my characters in Blender. That’s something I need to learn to improve. I’d also like to maybe add some people into it or rig any object to add more movement into the artwork.

BW: What is your favorite book?

QC: My favorite book is probably Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer. It’s incredibly well-written; I love how he describes spaces and rooms—it really packs a punch and has a cosmic horror vibe, similar to HP Lovecraft. I also really like Dune. I’ve read every Dune book about four times. I love the architecture in the film adaptation by Denis Villeneuve—it’s very brutalist, right up my alley. Absolutely gorgeous.

For updates on all of our upcoming editorial features and artist interviews, subscribe to our newsletter below.